Strengthening Indo-UK Defence Ties: Pathways to Co-Development in the Post-CEPA Era

The India-UK Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), signed in May 2025 after five years of negotiations, has emerged as a cornerstone for bilateral economic revival, with trade volumes surging 15% in the first half of the fiscal year. Beyond tariffs and market access, CEPA’s defence chapter—encompassing technology transfer, joint ventures, and supply chain integration—signals a paradigm shift in Indo-UK strategic ties. As both nations navigate a multipolar world marked by Indo-Pacific tensions and supply chain disruptions, co-development in submarines and fighter jets stands poised to redefine mutual security interests. This article delves into the historical evolution, post-CEPA opportunities, challenges, and a forward-looking roadmap for 2026 joint exercises, emphasizing shared benefits in regional stability.

Historical Context: From Colonial Legacies to Strategic Convergence

Indo-UK defence relations trace back to the post-independence era, with early collaborations in training and equipment under the 1949 Treaty of Peace, Friendship, and Cooperation. The 21st century marked a thaw: the 2004 Strategic Defence Partnership laid groundwork for joint exercises like Konkan (naval) and Rajkumar (air), evolving into the 2015 Joint Defence and Security Cooperation Framework. By 2021, Prime Ministers Modi and Johnson elevated ties to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, focusing on maritime domain awareness and information fusion centres.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2022 accelerated diversification, with India seeking alternatives to Russian platforms amid sanctions. The UK’s 2021 Integrated Review positioned India as a key Indo-Pacific partner, leading to the 2024 Roadmap 2030, which prioritized co-production in drones, cyber, and propulsion. Recent milestones include the July 2025 Vision 2035 roadmap, announcing pacts for complex weapons, jet engines, and warship propulsion. This historical arc—from buyer-supplier dynamics to equal-footed innovation—sets the stage for CEPA’s transformative role, where defence exports grew 20% year-on-year, reaching £500 million by Q3 2025.

Key inflection points include the 2025 Aero India agreements, launching Defence Partnership India (DP-I) and deals for ASRAAM missile assembly in Hyderabad by MBDA UK and Bharat Dynamics Limited (BDL). These not only arm India’s Su-30MKI fleet but enable global exports, aligning with Atmanirbhar Bharat’s indigenization targets of 70% by 2027.

Opportunities in Tech Transfer: BrahMos Exports and Tempest Collaboration

Post-CEPA, tech transfer forms the bedrock of co-development. BrahMos Aerospace, the Indo-Russian supersonic cruise missile JV, exemplifies potential UK integration. While primarily Indo-Russian, the UK’s October 2025 £350 million missile deal with India—delivering Brimstone NG variants—opens avenues for BrahMos co-production lines in UK facilities, enhancing export compliance under MTCR. With BrahMos’s combat-proven efficacy in Operation Sindoor (May 2025), UK firms like BAE Systems could adapt its seeker tech for Storm Shadow upgrades, fostering a £1 billion export pipeline to QUAD allies.

The Tempest program, the UK’s sixth-generation fighter under Global Combat Air Company (GCAP), beckons deeper collaboration. India, developing its Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA), eyes Tempest’s adaptive engines and AI-driven avionics. Rolls-Royce’s April 2025 offer for joint production of 110kN engines—coupled with Safran’s IP-sharing openness—positions the UK as a frontrunner over US GE F414 delays. A proposed Indo-UK Tempest-AMCA JV could involve HAL and BAE Systems co-designing stealth composites, targeting prototypes by 2030 and reducing India’s import dependency from 60% to 30%.

“Innovation and co-development are key priorities,” stated the July 2025 roadmap, highlighting Electric Propulsion Capability Partnership (EPCP) and Jet Engine Advanced Core Technologies (JEACT).

Submarine domain offers naval synergies. The UK’s AUKUS-inspired SSN-AUKUS tech transfer could aid India’s Project-75I, with Babcock International proposing electric propulsion JVs worth £250 million. Integrating MT30 gas turbines (already powering Indian ships) into Scorpene-class upgrades would enhance interoperability, vital for IOR patrols.

- BrahMos Synergies: UK adaptation for maritime strikes, leveraging CEPA’s 74% FDI cap.

- Tempest-AMCA: Shared R&D on quantum sensors, eyeing £10B in co-production deals.

- Submarine Propulsion: EPCP for AIP systems, supporting Mazagon Dock’s next-gen builds.

These opportunities, amplified by CEPA’s eased FDI norms (up to 100% for strategic tech), project £10-15 billion in inflows by 2030, creating 50,000 jobs and bolstering green defence initiatives like hydrogen fuels.

Challenges: Navigating Supply Chain Integration and Geopolitical Hurdles

Despite promise, challenges loom. Supply chain integration remains fragmented: UK’s reliance on US components (e.g., F-35 tech) risks CAATSA sanctions for India, while Brexit-induced regulatory divergences complicate certifications. Historical trust deficits—stemming from colonial-era arms embargoes—necessitate robust IP safeguards; a 2025 IISS report flags 25% of JVs failing due to tech-hoarding fears.

Geopolitically, balancing QUAD commitments with UK’s NATO-first posture (per June 2025 Strategic Defence Review) could strain alignments amid China’s IOR assertiveness. Export controls under Wassenaar Arrangement further bottleneck BrahMos-Tempest hybrids. Mitigation strategies include bilateral “trust funds” for IP escrow and phased tech releases, as piloted in the ASRAAM facility.

Workforce skilling poses another barrier: India’s 1.5 million defence jobs contrast UK’s 150,000, demanding joint academies like the proposed Indo-UK Defence Tech Institute in Bengaluru. Economic asymmetries—UK’s £2.5 trillion GDP vs. India’s £3.5 trillion—risk unequal benefits, underscoring CEPA’s need for equitable revenue-sharing clauses in JVs.

Future Roadmap: 2026 Joint Exercises and Beyond

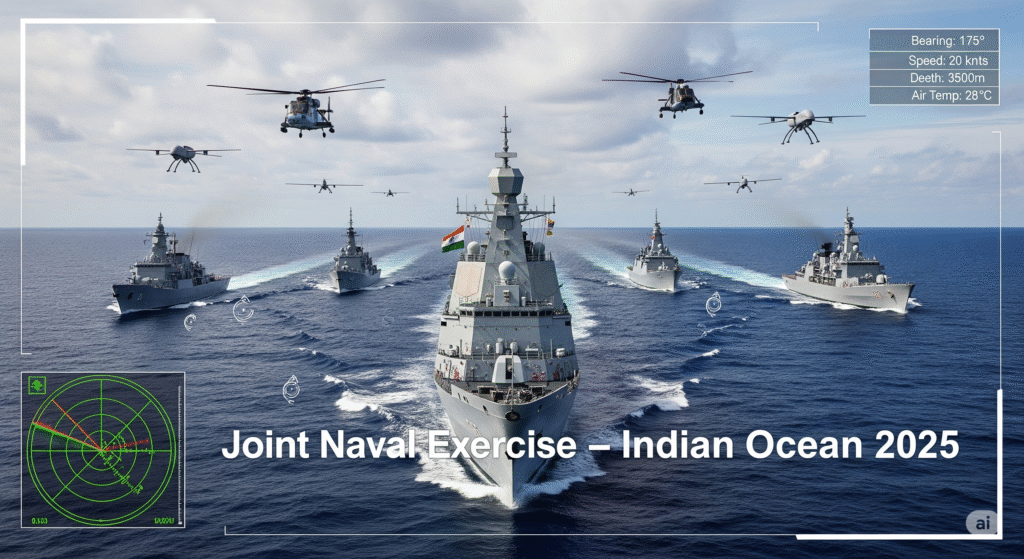

The 2026 roadmap envisions scaled-up joint exercises: Expanding Konkan to include submarine ops with INS Arighaat and HMS Astute, while air drills under Cope India integrate Tempest prototypes with Rafale-M. Tri-service maneuvers in the Arabian Sea will test BrahMos-Storm Shadow interoperability, fostering doctrinal alignment for hybrid threats.

Policy levers include a £500 million Indo-UK Innovation Fund for SMEs, targeting cyber-resilient submarines and AI-piloted jets. By 2028, aim for 40% co-developed content in AMCA squadrons, with exports to Commonwealth nations. Green tech integration—e.g., low-emission engines under EPCP—aligns with net-zero goals, positioning both as sustainable defence leaders.

Bilateral visits, like Starmer’s October 2025 Mumbai trip, underscore momentum, with MoUs for JEACT trials. As IISS analyses, these ties enhance deterrence: UK’s carrier deployments bolster India’s Andaman patrols, countering PLAN incursions.

Mutual Benefits: Indo-Pacific Stability and Economic Resilience

For India, co-development accelerates Atmanirbhar, slashing £8 billion annual imports and exporting £2 billion in JVs by 2030. The UK gains market access to India’s £70 billion defence spend, revitalizing firms like Rolls-Royce amid domestic cuts. Regionally, enhanced interoperability fortifies QUAD-plus frameworks, deterring aggression in chokepoints like Malacca Strait.

CEPA’s defence pillar transcends economics, embodying “mutual trust” as opined in ET commentaries. By weaving BrahMos precision with Tempest stealth, Indo-UK ties forge a resilient Indo-Pacific, where shared innovation yields enduring peace.

In this post-CEPA era, the partnership isn’t merely transactional—it’s transformational, promising a secure tomorrow through collaborative strength.